How Digital Annotations Challenge Historians’ Assumptions

In the five years since the project’s inception students and employees of the Seward Family Digital Archive have turned over every historical stone to find the people, places, and literature mentioned in the Seward Family Papers. As a research associate of the project, I can attest to the often tiring, tedious, and difficult labor that goes into recreating the Seward Family social network. This work, long known to documentary editors, gives depth to the manuscripts. However, with the adaptation of digital tools, the Seward Family Digital Archive sheds new light on to the interwoven relationships this nineteenth-century family experienced on a daily basis. Digital tools challenge traditional narratives and overturn long-standing characterizations of the Seward family.

For example, past historians define Frances Seward’s public persona as a defining factor of her social life. Frances has been depicted as “retiring” and as a “reclusive” wife who “plainly disliked prescribed socializing.”[1] As a result she has been portrayed as a woman who would rather spend time alone than connect to the world around her. Such critiques demonstrate a perceived expectation of married women throughout nineteenth-century America that conceptualized “separate spheres” for men and women. However, an examination of her letters aided by textual analysis reveals a different Frances.

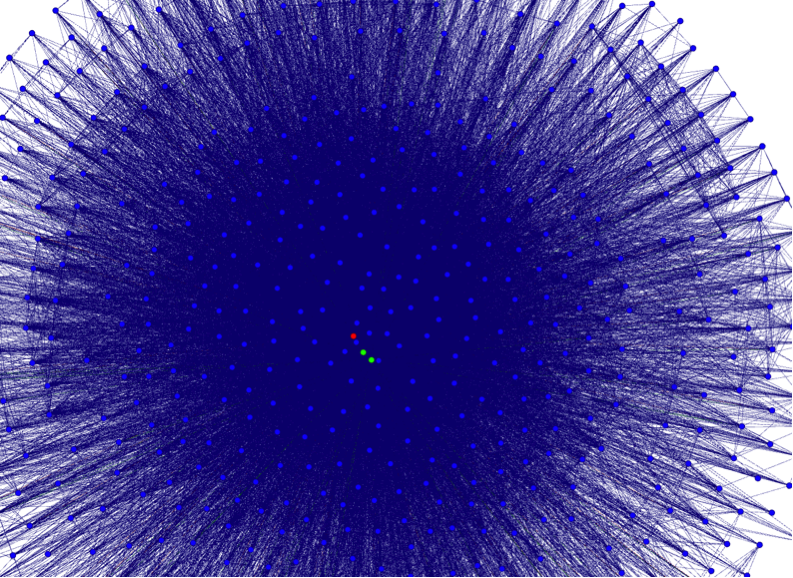

With digital technologies, we can count, connect, and illustrate that Frances existed in a larger sphere of men and women. Programs such as Gephi demonstrate that over the course of twelve years (1830-1842) Frances mentioned more than nine hundred unique individuals in her letters. Such numbers are staggering in the face of previous claims that painted Frances as a socially awkward and withdrawn. She discusses different politicians, a plethora of authors, gossips to friends, and serves as the central hub of communication for her family—hardly a recluse.

Such revelations are made possible through the use of digital tools. As the project continues to grow, more annotations will increase the family’s social network. From the date collected historians and students can ask new questions and continue to challenge longstanding or inaccurate perceptions of the Seward Family.

[1] Walter Stahr, Seward: Lincoln’s Indispensable Man (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2012), 324; Trudy Krisher, Fanny Seward: A Life (Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 2015), 80-81.

Camden Burd is a PhD candidate in the Department of History at the University of Rochester. He is a 2016-2018 Andrew W. Mellon Fellow in the Digital Humanities.