At the American Historical Association’s annual meeting in early January, digital humanities and digital history projects were some prominent buzzwords around the Marriott and Hilton Hotels in the form of panels, presentations and small conversations. It was a “nice to meet you” conversation that stuck with me the most, though. It went like this:

Serenity: Hi, I work on a digital humanities project at the University of Rochester.

Stranger: Oh? What project do you work on?

Serenity: I’m digitizing the papers of William Henry Seward’s family communication. We’re transcribing, annotating and editing thousands of letters from the 1830s to 1870s with the goal of displaying them on a website.

Stranger (skeptical): Are digitizing projects considered digital humanities?

Serenity (with slight indignation): Why, yes! It’s making accessible documents to a wider audience via a digital platform.

Stranger: When I use the website am I doing the digital humanities?

Serenity: ….ummm….

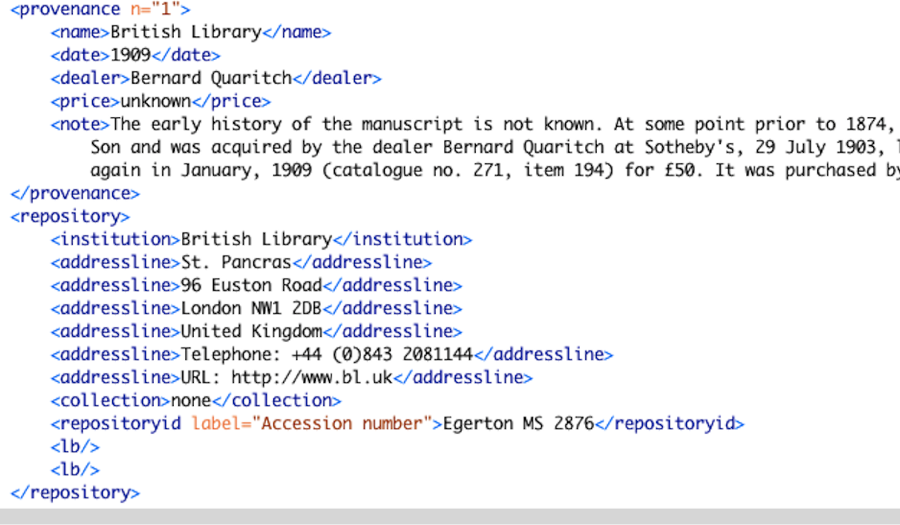

I eventually acceded in my teeniest, tiniest voice that “yes” the stranger was doing digital humanities when using the website. But in the back of my mind I wanted to protest that “NO!” there was a difference between consuming easily all of the legwork it took to actually get that content on the website: the wrangling of data, images, tagging in tei, three versions of editing, annotation, and transcription – all very hard work. Those of us on the project were hard at work producing the work of digital humanities. The end-user was merely consuming our digital humanities work.

To make sense of my responses to these questions of when one was “doing” digital humanities, I returned to Patrik Svensson’s article “Beyond the Big Tent” in Debates in the Digital Humanities (2012, digital edition). Basing his critique off of the 2011 Stanford digital humanities conference theme “Big Tent Digital Humanities,” Svensson concludes that asking who’s in and who’s out, or what DH project are or aren’t included in the Big Tent of the Digital Humanities, may not be the best way to visualize what we are doing and what’s at stake in DH. Svensson argues instead for a concept of a “trading zone” or “meeting place” to symbolize the types of work digital humanists do. I’ll discuss the usefulness of these terms later on, but first I want to unpack my “slightly indignant” response in the exchange above.

My colleague’s first question of “Are digitizing projects digital humanities?” stems from my sense that many hard-core DH-ers see the digitization of archive materials as simply “baby” projects that fail to adequately reflect the level of tech that DH can and perhaps should do. This is part and parcel of the Big Tent philosophy where one method of exclusion of who’s inside the flaps of the tent and who’s out, peeking through the cracks of the tent, is based on the tools one uses. As Svensson points out:

While tools themselves can be epistemologically predisposed, it could be argued that placing tools and tool-related methodology at the base of digital humanities work implies a particular view of the field and, within big-tent digital humanities, possibly an exclusive stance. One central question is whether the tent can naturally be taken to include critical work construing the digital as an object of inquiry rather than as a tool.

With this in mind, I’m inclined to lean towards Svensson’s portrayal of DH as either a “trading zone” or “meeting place,” but then these have implications for the question of consumer and producer, the origin of my second hesitation during my conversation at the AHA.

Trading zone implies that groups of people are present to do business and make exchanges. These exchanges are built on producer and consumer models where one person brings their items to trade for another items: ten pomegranates for one knitted hat. In this exchange there are given producers and consumers. And all parties likely had to “produce” something, be it labor for money or the actual product itself and in this case, all members of the trading zone are producers and consumers in one way or the other.

Meeting places, on the other hand, send a more democratic or egalitarian message. Meeting places are where people come to be heard and to be listened to. I’m not sure that meeting places eliminates the producer/consumer question, though, as I’ve surely attended meetings intending to contribute very little, only to listen and learn. In this situation, I’m entirely consuming the meeting’s content, perhaps for my own future production of work, but perhaps not. I’ve also led meetings where I do much of the talking while participants scribble down notes to take with them, consuming what I say to put into use elsewhere, or else, to fall into a recycling bin a few months later as they clean out their desks.

So while Svensson’s retooling of the Big Tent into meeting place or trading zone alleviates the question of who’s in and who’s out, the metaphors may be too limited for helping me make sense of the consumer/producer of digital humanities.

To better understand this idea of consumer and producer in an academic context, I look at one of the West’s most cherished forms of academic communication: the book. When scholars produce books, they spend a great deal of time researching and thinking about their topic, not to mention agonizing late nights writing and communicating their thoughts clearly. Just because I read a book on North American sparrows, obviously, does not make me a scholar on sparrows or any other kind of bird. However, reading many books, doing a good amount of field research, and attending classes and conferences on ornithology does. Someone who reads a book on the reign of Queen Elizabeth I would hardly be qualified as “doing” monarchical history solely by reading the book. In academia, one only validly “does” monarchical history by reading many texts on kings and queens, and producing research that contributes to the current conversations about the topic.

All this to say, that in my mind, the question of who “does” DH depends on the types of questions we employ to make sense of a digital resource. Digital Humanities projects are like other source material: how we use them depends on the questions we ask and the furthering of knowledge that results. Scholars doing digital history may have a variety of questions ranging from how the digital informs our reading of the manuscripts to where issues of gender, medical, family, political and social history find resonance by searching the database with keywords. Using a digital resource to answer these questions is more a question of “doing” intellectual work in general, rather than a question of “doing” the digital. And this, for me, is where John Unsworth’s concept of “Scholarly Primitives” is useful. Good scholars are both producing and consuming knowledge through “Discovering, Annotating, Comparing, Referring, Sampling, Illustrating and Representing”

I do think the question of production vs consumption in DH is one that requires further unpacking and really parallels, if not entwines, questions of labor and reward for work. Especially in the example above, I balked at including the consumer as “doing” DH when I thought of the hard, hard work organizing, transcribing, annotating, editing and tei-ing the Seward letters. It struck me rather unfairly that that the consumer’s labor of “doing” DH was not the same as my labor “doing” it. The question of labor is not limited to producer/consumer, though. For many DH projects I know of, an extensive amount of library support is required for any of these projects to get off the ground. Programmers, librarians, support staff, (not to mention shamelessly exploited undergrads and grads!) all do a good amount of work to help academic humanists produce fancy projects to begin with. Where is their recognition and pay-off for such labor? Is it fairly equitable with the principle investigators and academics who will go on and use the project to build their CVs, argue for tenure, raises, or other recognitions? Is an hourly, somewhat livable, wage recognition enough for the support staff that assists our technically heavy projects? Where do “digital” acknowledgment sections get us?

Perhaps the next blog post?

—

Serenity Sutherland is a PhD student in the Department of History at University of Rochester.

For the past few months, I have served on the steering committee for a proposed Extended Reality (XR) space on the University of Rochester’s River Campus. My tenure as an Andrew D. Mellon Fellow in Digital Humanities has provided me with many opportunities to engage with a broad range of digital tools and techniques aimed at research and teaching. The steering committee, however, has been an opportunity to be involved in the nuts and bolts process behind the development of new digital spaces and opportunities for the university community. As I quickly discovered, this process calls for a very different set of skills than either research or teaching. The process of consulting the various stakeholders, carefully designing charrettes to elicit useful and valuable feedback, and developing a coherent proposal for a functional, accessible space that meets those needs was an enlightening departure from my normal role as a passive user of university spaces and amenities. The vast majority of the credit must go the the committee leader, Director of Research Initiatives, Lauren Di Monte, who brought her extensive experience and knowledge to the process and has taught me a great deal about the skills and careful design that goes into the process.

For the past few months, I have served on the steering committee for a proposed Extended Reality (XR) space on the University of Rochester’s River Campus. My tenure as an Andrew D. Mellon Fellow in Digital Humanities has provided me with many opportunities to engage with a broad range of digital tools and techniques aimed at research and teaching. The steering committee, however, has been an opportunity to be involved in the nuts and bolts process behind the development of new digital spaces and opportunities for the university community. As I quickly discovered, this process calls for a very different set of skills than either research or teaching. The process of consulting the various stakeholders, carefully designing charrettes to elicit useful and valuable feedback, and developing a coherent proposal for a functional, accessible space that meets those needs was an enlightening departure from my normal role as a passive user of university spaces and amenities. The vast majority of the credit must go the the committee leader, Director of Research Initiatives, Lauren Di Monte, who brought her extensive experience and knowledge to the process and has taught me a great deal about the skills and careful design that goes into the process.

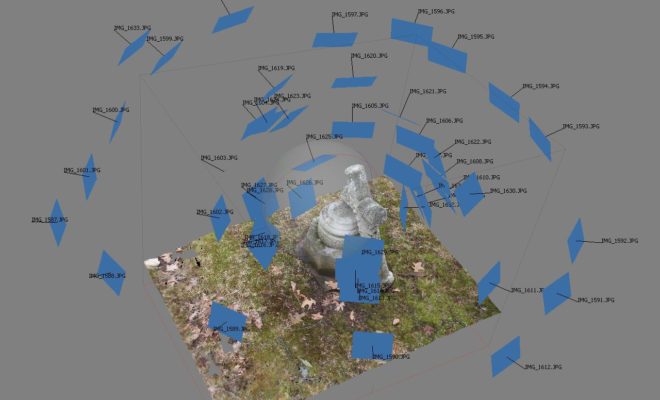

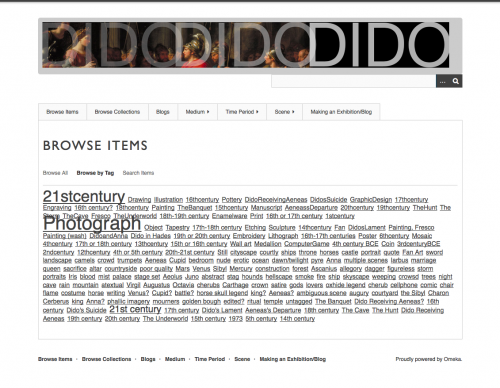

Having pre-arranged specific Omeka accounts of for each of the 31 participants at the workshop, Victoria launched into the goal for today: to create an interactive display of notable graves in the nearby Mt Hope cemetery. We all signed up for a particular grave on a shared googlesheet, and got to work adding images as items and writing up funny (or not) captions and accompanying text. The first hour of the workshop was consumed with the business of creating these and adding tags, collecting them within new exhibits, producing relevant (or not) metadata, and otherwise exploring the basic functionality of the site. Meanwhile Victoria was everywhere around the room, helping those who were stuck, suggesting new or better choices, and prepping for the next stage.

Having pre-arranged specific Omeka accounts of for each of the 31 participants at the workshop, Victoria launched into the goal for today: to create an interactive display of notable graves in the nearby Mt Hope cemetery. We all signed up for a particular grave on a shared googlesheet, and got to work adding images as items and writing up funny (or not) captions and accompanying text. The first hour of the workshop was consumed with the business of creating these and adding tags, collecting them within new exhibits, producing relevant (or not) metadata, and otherwise exploring the basic functionality of the site. Meanwhile Victoria was everywhere around the room, helping those who were stuck, suggesting new or better choices, and prepping for the next stage.